Heart surgery isn’t something most people think about until it’s suddenly needed. Whether it’s a bypass, valve repair, or stent placement, the decision to operate isn’t made lightly. Doctors don’t just look at your chest pain or ECG-they weigh a whole list of hidden risks. Some people can walk through surgery with minimal trouble. Others face a much higher chance of serious problems. So who exactly is high risk for heart surgery?

Age isn’t just a number-it’s a major factor

People over 75 have a significantly higher chance of complications after heart surgery. That’s not because older bodies are weak, but because aging changes how organs respond to stress. The heart muscle thickens, blood vessels stiffen, and kidneys don’t filter as well. A 78-year-old with aortic stenosis might need surgery to live, but their body has less reserve to handle the trauma of open-heart procedures.

Studies from the American Heart Association show that patients over 75 have nearly double the risk of kidney failure, stroke, and prolonged ICU stays compared to those under 65. It’s not that surgery is off the table-it’s that doctors need to plan differently. They might choose a less invasive option like TAVR for aortic valve replacement instead of open surgery. Or they’ll run extra tests to check lung and kidney function before moving forward.

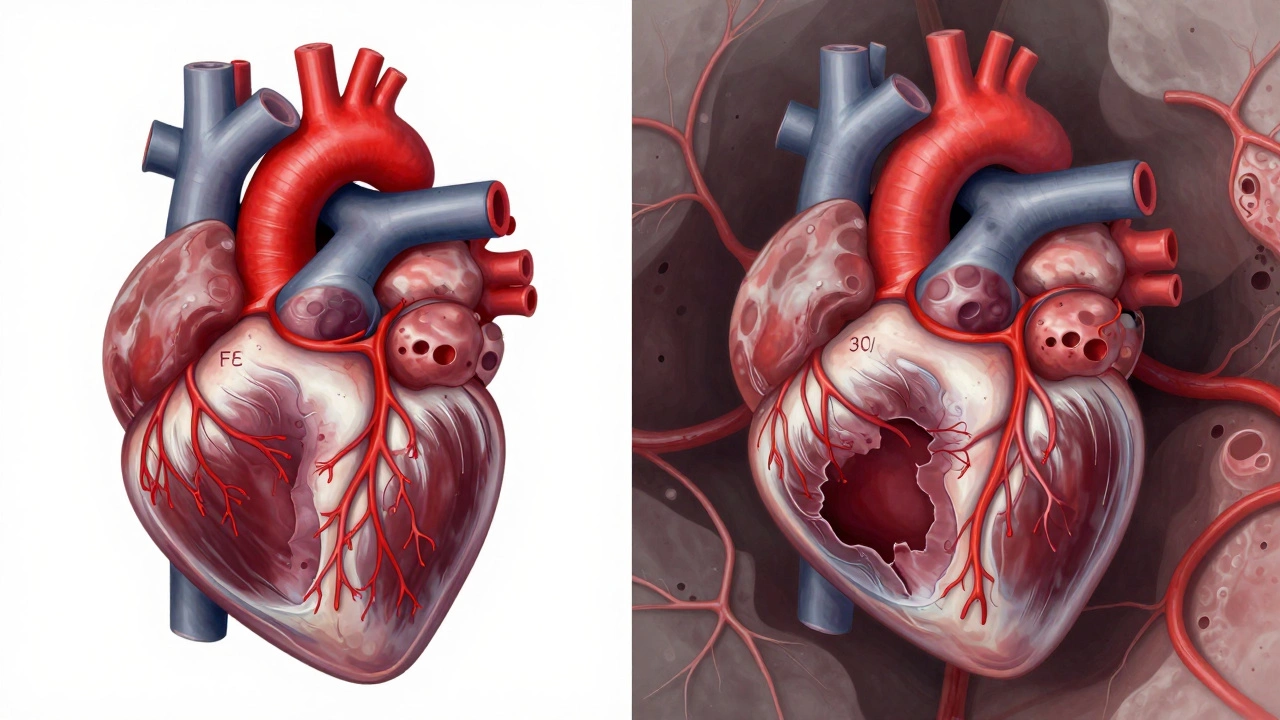

Previous heart damage changes everything

If you’ve had a heart attack in the past, especially within the last six months, your risk jumps. Scar tissue from damaged heart muscle doesn’t pump well. When you put that heart under the stress of surgery, it can struggle to keep up. A patient with a prior heart attack and an ejection fraction below 30% is considered high risk because their heart is already working at 70% capacity just to stay alive.

Doctors measure this with an echocardiogram. If your heart is pumping out less than 35% of the blood it should, surgery becomes more dangerous. That’s why some patients with severe heart failure are first treated with medications, ICDs, or even LVADs before even considering surgery. Pushing too soon can lead to cardiac arrest during or right after the operation.

Diabetes makes healing harder-and risk higher

Diabetes isn’t just about sugar levels. It quietly damages blood vessels, nerves, and immune function. A diabetic patient undergoing bypass surgery has a 40% higher chance of developing a deep infection at the incision site. Their wounds heal slower. Their arteries are more likely to clog again after bypass grafts.

Research from the New England Journal of Medicine shows that diabetics have a 2.5 times greater risk of death within 30 days after heart surgery compared to non-diabetics. It’s not that they can’t have surgery-it’s that their blood sugar must be tightly controlled for weeks before the procedure. Even a single day of high glucose can increase infection risk. Surgeons often delay surgery until HbA1c levels drop below 7.5%.

Lung disease turns heart surgery into a life-or-death gamble

If you have COPD, severe asthma, or pulmonary fibrosis, your lungs are already struggling. Heart surgery requires you to be on a ventilator for hours, sometimes days. If your lungs are weak, they can’t handle the extra load. Many patients develop pneumonia or need long-term oxygen support after surgery.

One study of over 12,000 patients found that those with moderate to severe lung disease had a 37% higher chance of dying within a year after heart surgery. That’s why doctors test lung function with a simple spirometry test before approving surgery. If your FEV1 is below 50% of normal, they’ll often refer you to a pulmonologist first. Sometimes, a lung rehab program can improve your chances enough to make surgery safer.

Obesity isn’t just about weight-it’s about metabolic strain

People with a BMI over 35 are considered high risk, but it’s not just the extra pounds. Obesity causes chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and high blood pressure-all of which make surgery riskier. Fat tissue around the heart can make access harder during surgery. The risk of blood clots, wound infections, and breathing problems goes up significantly.

Surgeons often see obese patients develop deep sternal wound infections after bypass surgery. These infections can go deep into the bone and require multiple surgeries to clean out. Weight loss before surgery isn’t always possible, but even losing 5-10% of body weight can reduce complications. Some hospitals now require patients to join a pre-op nutrition program if their BMI is above 40.

Kidney problems are a silent red flag

Your kidneys help flush out anesthesia, contrast dye, and surgical toxins. If they’re already damaged-say, from high blood pressure or diabetes-your body can’t clear these substances efficiently. This leads to acute kidney injury, which happens in up to 20% of heart surgery patients.

Doctors check creatinine levels and eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate) before surgery. If your eGFR is below 45, you’re in the high-risk zone. Dialysis patients face the highest risk-nearly half don’t survive the first 30 days after heart surgery. In these cases, surgeons often coordinate with nephrologists to time dialysis around the procedure and avoid contrast dyes when possible.

Other hidden risks you might not realize

There are less obvious factors that push someone into the high-risk category:

- Smoking: Even if you quit a month ago, your lungs and blood vessels are still recovering. Surgeons prefer patients to be smoke-free for at least 6-8 weeks before surgery.

- Chronic anemia: Low red blood cell count means less oxygen delivery during surgery. Many patients need iron infusions or even transfusions before the operation.

- History of stroke or TIA: If you’ve had a stroke in the past year, the risk of another one during surgery is much higher. Doctors may delay surgery or use special techniques to protect brain blood flow.

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure: Blood pressure spikes during surgery can cause bleeding or heart rupture. It must be stable for at least 2-4 weeks before the procedure.

- Recent infection: A bad cold, pneumonia, or even a urinary tract infection can delay surgery. Your immune system needs to be calm before facing major trauma.

What happens if you’re high risk?

Being labeled high risk doesn’t mean surgery is off-limits. It means the team needs to plan more carefully. Many hospitals now use risk prediction tools like the STS Score (Society of Thoracic Surgeons) to calculate your chance of death or major complications. This score combines age, kidney function, lung health, and other factors into a single number.

If your risk is high, you might get:

- A less invasive option (like TAVR instead of open valve replacement)

- More pre-op testing (stress tests, lung function, blood work)

- A longer hospital stay for closer monitoring

- Specialized teams (cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and intensivists working together)

- Post-op rehab programs tailored to your needs

Some patients choose to avoid surgery altogether if their quality of life isn’t severely affected. Others accept the risk because the alternative-untreated valve disease or blocked arteries-is worse. The decision isn’t about being brave or scared. It’s about understanding your body’s limits and choosing the path that gives you the best shot at living well.

Can you lower your risk before surgery?

Yes-sometimes dramatically. Here’s what works:

- Quit smoking now. Even 3 weeks without nicotine improves blood flow and healing.

- Control your blood sugar. Work with your doctor to get HbA1c under 7.5%.

- Start light exercise. Walking 20 minutes a day improves heart and lung endurance.

- Reduce salt and processed food. This lowers blood pressure and fluid retention.

- Treat infections before surgery. Don’t rush in with a cough or fever.

One patient I worked with-a 72-year-old with diabetes, COPD, and a BMI of 38-delayed his bypass for 10 weeks. He lost 12 pounds, quit smoking, and did daily breathing exercises. His risk score dropped from 18% to 9%. He walked out of the hospital in five days.

Is heart surgery safe for elderly patients?

Yes, but only when carefully planned. Age alone doesn’t disqualify someone. Many patients in their 80s have successful heart surgeries today thanks to better techniques and pre-op care. The key is assessing overall health-not just age. A healthy 80-year-old with no lung or kidney issues can do better than a 65-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

Can you have heart surgery after a stroke?

It depends on timing and recovery. If the stroke was recent (within 3 months), surgery is usually delayed to avoid another one. After 6 months, with no lasting damage and stable blood pressure, surgery can be safe. Doctors use brain imaging and neurological exams to decide. The goal is to avoid triggering another clot during surgery.

Does being overweight automatically mean I’m high risk?

Not automatically. A BMI over 35 increases risk, but it’s not the only factor. Someone with a BMI of 37 but great lung function, normal blood sugar, and no diabetes may have a lower risk than a thinner person with uncontrolled hypertension and kidney disease. Surgeons look at the full picture-not just weight.

What’s the most common complication in high-risk patients?

Kidney injury is the most common serious complication. About 1 in 5 high-risk patients develop acute kidney damage after surgery. This often happens because of contrast dye, low blood pressure during surgery, or pre-existing kidney weakness. Doctors now use less dye, keep fluids balanced, and monitor urine output closely to prevent it.

Are there alternatives to open-heart surgery?

Yes, and they’re becoming more common. For valve problems, TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) is now standard for high-risk patients. For blocked arteries, PCI (angioplasty with stents) can replace bypass in some cases. These are less invasive, done through small cuts in the groin, and often require shorter recovery. But they’re not always the right choice-your doctor will compare your anatomy and risks to pick the best option.

Final thought: Risk isn’t a yes-or-no answer

There’s no single test that says, “You’re too risky for surgery.” It’s a mix of age, health history, lab results, and how your body responds to stress. The goal isn’t to avoid surgery at all costs-it’s to make sure you’re as prepared as possible. If you’re told you’re high risk, ask for a detailed breakdown of your numbers. Ask what steps can be taken to lower those risks. And don’t let fear stop you from getting the care you need. Many people who were told they were too high risk ended up living years longer because they chose to act-with the right support.